No one wants to talk about the possibility of failure. But there is much to learn from the entrepreneurs who risked it all and didn’t come out on top

The decision to close her plant-based dessert brand Pudology came to founder Lucy Wager with striking clarity back in 2019. “One morning I’d just found out the date we were coming out of Sainsbury’s, and I thought, I can’t do this any more,” she remembers. I didn’t want to risk more money. I was so joyless. I needed to do something else.”

It had been seven years since Wager, previously a product developer for both Sainsbury’s and M&S, begun making the chilled vegan desserts in a tiny, shared kitchen unit, buoyed by the support of entrepreneurial parents. After she had unveiled the products at London’s Allergy & Free-From Show, success followed fast. She quickly began selling through a wholesaler before landing listings in Selfridges, Ocado, Waitrose, Sainsbury’s and Tesco. The team grew and desserts were flying out of the manufacturing facility in their thousands. “There was always good news,” she remembers of that time.

“Founders often believe they need to work 24/7 and not take a salary”

In 2018, though, the market began to shift. Copycat products with a lower price tag showed up on shelves. It was issues with shelf life that saw the brand delisted from Sainsbury’s. And “we couldn’t compete with larger brands from a marketing perspective. I knew to continue we’d need further investment, and I didn’t know if I’d ever get that back.” The brand entered administration in October the following year.

90%

of startups fail within the first three years of operation

Startup Genome Project

“I’ve got memories of holding my second child and crying,” says Wager. “I was worrying about money and looking at this tiny baby feeling so torn. It was awful. I had no idea what I was going to do, and I felt like a complete failure. I felt like nobody would ever want to work with me again.”

They did, of course. Wager now works as a successful startup consultant in the food sector. But that journey may have been eased by a bit more openness around the realities of entrepreneurship.

Talking about failure

The truth is that most ventures in food will fail. It’s thought some 90% of startups quietly close within the first three years – with retail and food consistently among those sectors with the highest rates of failure.

In the past year alone, multiple brands – from challengers to 120-year-old heritage names – have entered administration. Yet, it’s a side of brand building rarely talked about, buried beneath the headlines of hit product launches and multimillion-pound funding rounds. And there are lessons every bit as valuable to be learned from failure as success.

So, what’s it like to pour yourself into a business that ultimately doesn’t make it? What lessons do founders walk away with?

“There needs to be more openness about the fact that things can go wrong and that it’s quite terrifying when it does,” says Julia Kessler, founder of soft drinks brand Nix and Kix, which was acquired by Amsterdam-based group Good Food Vibes from administration in October. “When it’s at a high, it feels amazing. But when it isn’t, the experience is terrifying. I’m still trying to recover from it.”

Five brands that hit the buffers in the past year

Allplants

Launched: 2016

Founder: Jonathan Petrides

Filed for administration: November 2024

What happened: Frozen ready meal challenger Allplants officially entered administration late last year, with 65 staff losing their jobs and investors facing losses of almost £70m. Having raised £67m from VC firms and crowd investors, and scaled to 100-plus retail outlets, the brand had struggled to sustain revenue growth while costs mounted. The brand won’t disappear, however, having been bought out of administration by Deliciously Ella founder Ella Mills in February this year.

Gunna

Launched: 2016

Founder: Melvin Jay

Filed for administration: January 2025

What happened: Gunna launched its range of craft flavoured lemonades in 2016. The better-for-you brand caught the eye of investors, with Gunna raising £3.1m across five crowd rounds from 1,400 backers on Republic, then known as Seedrs, from 2019 to 2022, and another £820k from 245 investors on Crowdcube in 2018. However the brand had racked up millions in accumulated losses. “A lack of funding and strategy meant that Gunna struggled to make the brand a success,” said Andy Pear, Moorfields partner and joint administrator.

Jones Food Company

Launched: 2018

Founder: James Lloyd-Jones

Filed for administration: April 2025

What happened: Only last year, Jones Food Company opened its second state-of-the-art vertical farm in Gloucestershire. At the time, founder Lloyd-Jones said it had “cracked the code for accessible, sustainable, premium food being grown all year round, at a super-competitive price”. But at news of its collapse last month, commentators described it as “inevitable” given the structural challenges faced by businesses looking to turn a profit from the precision farming model.

Square Root

Launched: 2012

Founders: Robyn Simms and Ed Taylor

Filed for administration: September 2024

What happened: Four years after craft soda brand Square Root made its retail debut in Sainsbury’s, it was forced to appoint administrators. Having successfully raised almost £900k from close to 700 investors on Seedrs over two rounds in 2021 and 2022, co-founder Simms told The Grocer the business was unable to secure further equity investment to overcome working capital challenges. It isn’t the end for the brand, though, with Taylor leading a pre-pack deal to buy his company back.

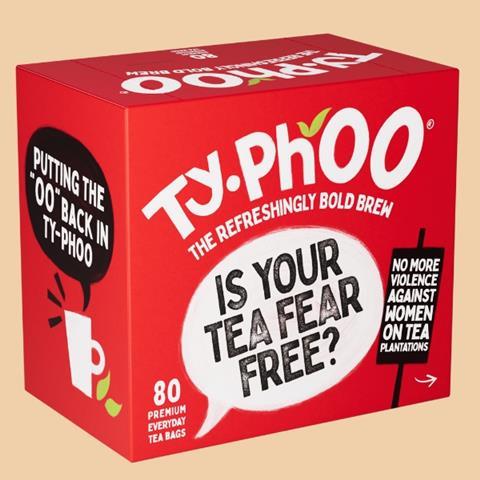

Typhoo

Launched: 1903

Founder: John Sumner

Filed for administration: November 2024

What happened: Proof that it isn’t only challenger brands that hit hard times, 120-year-old brand Typhoo Tea collapsed late last year, having seen losses balloon to almost £40m after trespassers broke into one of its factories in 2023. It was one of a series of setbacks the brand faced, as consumers turned away from traditional black teas to coffees and herbal infusions. Typhoo’s revenues fell from £82m in 2014/15 to just £25.3m in 2022/23 as a result. The brand owed its creditors close to £100m at the time of its collapse.

The food industry doesn’t talk about failure nearly enough, she says. Kessler had been working in tech when she and co-founder Kerstin Robinson set up Nix & Kix in 2016. “I was quite naïve,” she says. “People come up with a great idea at the kitchen table and then know really nothing about how to scale it.”

The pair changed manufacturers multiple times and had to experiment with different sales segments before they found the right fit, pivoting from bars and coffee shops to a mix of retail and hospitality.

“Then we really took off,” remembers Kessler, who found herself signing deals with major supermarkets and foodservice providers. From 2018 to 2020, the brand “scaled really well and really fast. It was an amazing amount of fun.”

10%

of women are now engaged in early-stage entrepreneurial activity – a threefold increase since 2002

Natwest Group

But then came Covid. Overnight, 70% of the brand’s business dried up and an “incredibly challenging” pivot to direct-to-consumer followed. Investors stopped adding to the pot, and a terrible summer in 2024 saw the brand fall shy of its revenue projections, leaving three months’ worth of stock sat in a warehouse. Administrators were called in shortly after.

“You feel incredibly guilty as a founder when you get into that situation,” says Kessler. “I did and I do. I still feel responsible for what happened. And there isn’t an awful lot of support.”

“The feelings of failure were crippling,” agrees Cecily Mills, who launched Cecily’s Ice Cream (originally Coconuts Naturally) in 2015. She’d begun as a whirlwind “one-woman show with my little baby”, unveiling the vegan ice cream at the London Excel in April that year, with her four-month-old strapped to her in a carrier.

“It started this incredible amount of, I’d say, passion, momentum, drive, vision, focus, all of those things,” she says. Within two years, the business won a number of Great Taste awards and expanded from selling to local shops and cafés in Cornwall to supplying Ocado, alongside local listings with Morrisons and Asda. Then, in 2019, a deal with Tesco “kicked off this chain of events that became so unmanageable”, Mills recalls.

+23%

Between 2010 and 2024 the business population increased by one million

FSB

First, a new manufacturer pulled out two weeks before launch. Then Covid saw all promotions grind to a halt, triggering the loss of the brand’s place on Tesco’s shelves. And next, supply chain issues drove up costs and made packaging impossible to get hold of. “It was exhausting,” she says. “I was like: ‘What next?’”

The final nail in the coffin was cash. The brand wasn’t profitable and was therefore wholly reliant on investment to push through. But when Mills came to contemplate its annual funding round, she couldn’t face it. “I got to the point where I was thinking: ‘I have to just live for myself and my two girls now. I can’t keep going with this.’” The brand finally closed its doors in 2022.

The personal impact of that type of decision – emotionally, professionally and financially – can be profound, insists Thea Brook, who closed her own ready meal brand The Brook in 2022. “It was incredibly painful,” she says. “Especially in food, where businesses are often born from deep passion, it feels like such a personal loss. It’s so tied to your identity that it doesn’t just feel like a business failing, it feels like you’ve failed.”

Battles, mistakes and lessons learned

Though The Brook emerged from Covid with “two strong and growing revenue streams” in retail and home delivery, changes to Facebook advertising soon after affected its e-commerce growth.

“Then, as we were navigating that challenge, the cost of living crisis hit in 2022,” says Brook. “As a food business, we were hit from all sides – rising ingredient costs, energy bills tripling and consumers tightening budgets. It was a perfect storm that tested every part of the business. I lost half a million pounds when the business closed and my health took a real hit. I’d poured everything into it.”

Be it Covid, costs or the whims of buyers, many battles brands have faced in recent years have been beyond their founders’ control. Others, though, reflect on the inevitable mistakes made when feeling your way into a complex, competitive sector like food and drink.

For example, were Wager to go back, she’d focus on what she was good at, she says, rather than attempting to oversee every single element.

“You spread yourself so thin that you don’t do anything very well,” she says. “I got so confused by the overwhelming amount that needed to be done in finance, logistics and every other aspect of the business that I totally lost sight of what I was actually good at. You can’t do everything.”

That’s echoed by Joe Woolf, who co-founded better-for-you confectionery brand Tasty Mates in 2021 with friend Nick Sunshine. The brand closed three years later after a series of setbacks that included the loss of a lucrative airline contract after the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

“Founders often believe they need to work 24/7 and not take a salary, but it’s really important when you’re building a forecast or planning your investment that you put in a salary for yourself, a realistic one,” Woolf says. “Otherwise, you’re going to get to a point where the pressure isn’t just on the business, it’s also on you outside of the business and that’s not sustainable. If I was to do a raise for a business now, I’d ringfence a salary.”

On the operational side, manage your costs and don’t get sucked in by the lure of a jam-packed product pipeline, adds Kessler.

“Every packaging change, every new piece of artwork, costs money and is difficult to manage from a supply chain perspective, too.

“Don’t have too many SKUs from the get-go either,” she adds. “We started with five flavours in three different formats and that’s a lot of inventory to manage. Founders always get really excited, me included, about launching a new product and a new flavour. You want new news to talk to your customers about. But if you have eight, 10 or 12 SKUs and the tail doesn’t perform, that makes your supply chain complicated and your demand planning really difficult.”

30%

Just under one in three UK adults now either run their own business or plan to start a business within the next three years

Natwest Group

Scrutinise new investors rather than fall for (what may turn out to be) empty promises, adds Greg Fraser, founder of The Bottled Baking Co, a baking brand that went into liquidation this week. The first-time food entrepreneur had signed a deal with a new investor and co-packer who “promised the world”, including cost reduction and simplified processes. In reality, shortly after the contract was signed, they doubled the minimum order quantities (MOQs) and removed the brand’s credit limit, leaving them with a £100k debt to repay up front. Coupled with rising ingredient costs, retail customers that wouldn’t budge on price (and ultimately delisted the range) and a large, expensive warehouse they ultimately didn’t need, Fraser says he faced “no option” but to file for administration.

“Scaling sustainably is so important, but it’s not what founders really want to hear,” reflects Mills. If she could turn back the clock, she says she’d focus far more on profitability. “If you don’t make money, then unless you’ve got an investor with really deep pockets that’s willing to back you round after round after round, the business is on thin ice.”

Structural barriers

It isn’t always founders that are responsible for making the changes required to boost success rates, though. For Asher Flowers, who entered insolvency with his spreads and cereal brand Rogue in 2022, there are also structural barriers that founders come up against. Rising costs, manufacturing capacity and the loss of an Asda listing left his brand seeking additional investment, but that proved an insurmountable challenge.

“If you look at the data on young, working-class founders of colour it’s very limited when it comes to raising capital,” he says. Any investor offers that were on the table came with valuations that would’ve left the brand completely diluted. “I felt like you could have a 10 out of 10 effort, but it’s still not driving the volume you need to build it into the thing you want to build it into,” he says. “It broke my heart.”

1/2

The share of brand-new food and drink launches hitting supermarkets has halved since 2013

Mintel

But, as Flowers puts it, “I didn’t have the capital or the time to lick my wounds.” Instead, he poured himself into his next venture, kicking off tequila brand Broken Barrier a month after closing Rogue and, in April 2024, setting up sales agency Lateish too. “I’m very pleased with what I achieved at Rogue. It led me to what I’m doing with Broken Barrier and to what I’m going to do in the future,” Flowers says.

He isn’t the only founder that dusted himself off after a difficult start and plunged straight back in at the deep end. And many have had significant success.

Before they set up Heck, founders Andrew and Debbie Keeble had started out with an eponymous sausage brand in 1999 that achieved spots in Tesco and Asda but then joined ranks with a larger firm.

“It was a disaster,” says Debbie Keeble of the partnership. “We were passed around three big corporations, who ran out of money, so we lost the brand. It was traumatic, and we had to start from scratch in our late 40s, but our kids were relying on us.”

The pair used the £700k compensation from their first business, which she says “felt like a big risk”, and in April 2013 launched their Heck sausages into Tesco.

“Today, we have £30m turnover and a range of food that crosses from bangers to burgers and mince and even sausage bacon, all stocked in major supermarkets,” she adds. “One of the things I learnt from Terry Leahy when he was at Tesco is how he never told people off if they made mistakes. In fact, he encouraged it, as that meant they would always be better. I agree with him – sometimes it’s got to go wrong to launch it in a better way. You don’t know what you don’t know, so it’s OK to make mistakes.”

Advising with empathy

For other founders, though, plunging themselves back into another brand launch hasn’t been the right path. At least, not yet.

Wager, Kessler and Woolf, for example, all work as consultants, mentors or advisers to the food sector’s startups. “Living through those highs and lows gave me a deep empathy for founders,” says Brook. “I know what it’s like to carry the weight of a team, navigate impossible decisions and feel the pressure to keep going. That’s why I now focus on helping other founders build strong, sustainable businesses – without burning out or overexposing themselves. I bring the finance expertise but also the lived experience of what it really takes.”

–1%

Between 2023 and 2024, the total business population decreased

FSB

Wager even co-hosts a podcast, ‘Oh For Food’s Sake’, where she discusses the industry’s trials and tribulations. “I really wanted a way of sharing the journey I’d been on and the lessons I’d learned,” she says.

Meanwhile, others have remained within the challenger space but without shouldering all the risk. Like Mills, who is now grocery controller at Biotiful Gut Health.

She does admit, though, that the entrepreneurial itch hasn’t quite gone away. “I’ve definitely got another business in me,” she smiles. “It was still incredible. I love this industry so much. Small brands can break the mould and that matters, it really matters. I’d definitely do it again. But I’d do it a lot differently. Even then, it might still be a failure, but you never know. You’ve got to keep trying.”

No comments yet